Many years ago, an organisation I used to work for had its values written all over the walls of its offices, on every PowerPoint slide and on every report and press release. The leadership team earnestly believed that their values articulated their culture, yet all around us was tangible evidence that the experience of working in that organisation was very far away from what they believed. It was more “cult” than “culture”. When organisations fail, “culture” is often named as the culprit. Failed IT projects, service breakdowns, or corporate scandals are routinely explained as “a cultural problem”, but this framing is misleading. Culture matters, but treating it as the root cause of every issue oversimplifies complex failures and lets leaders off the hook. Real transformation means tackling strategy, structures, incentives, and leadership—alongside culture, not instead of it. The Stewart Review (2025) which investigated the HS2 failures identified multiple systemic problems, among them cost escalation, schedule delay, and poor contract management but also pointed to the culture (top down vision, giving into political pressure and lack of challenge) as key causes of failure. There is rich field of examples:

- Healthcare IT projects where clinicians are often accused of cultural resistance, but many systems disrupt workflow, slow practice, and show little benefit. The “cultural barrier” is poor design and leadership.

- Banking scandals: After 2008, regulators cited “toxic culture.” But that culture was shaped by incentive structures that rewarded risky behaviour.

- Government programmes. Reports often describe a “culture clash” between civil servants and contractors. But the root causes are usually contract design, procurement rules, and accountability gaps.

Saying “the culture was wrong” sounds plausible but hides harder truths: poor governance, lack of process, confused strategy, or misaligned incentives. Culture is hard to challenge because unlike data or compliance breaches, “culture” is vague. Nobody can prove or disprove it, so it becomes a catch-all explanation.

Leaders often imply it’s “staff culture” that’s the issue, avoiding scrutiny of the very systems and behaviours they themselves shaped.

Culture change follows system change

Culture can be defined and described. Edgar Schein describes three layers: Artifacts – visible behaviours, rituals, language, Espoused values – what organisations claim to stand for, and Underlying Assumptions – unconscious beliefs that guide daily action. Culture is not just “how people behave,” but the accumulated patterns and assumptions shaped by structures and incentives. Change the system, and culture follows. “Fixing the culture” is often presented as the key to transformation. But culture is an outcome, not a lever you can pull in isolation. For example, If pay and promotion reward silos, no amount of “teamwork” slogans will matter. If decisions require endless sign-offs, agility will remain rhetoric. If leaders punish candour, staff will hide problems regardless of stated values.

Thinking about the framework for transformation

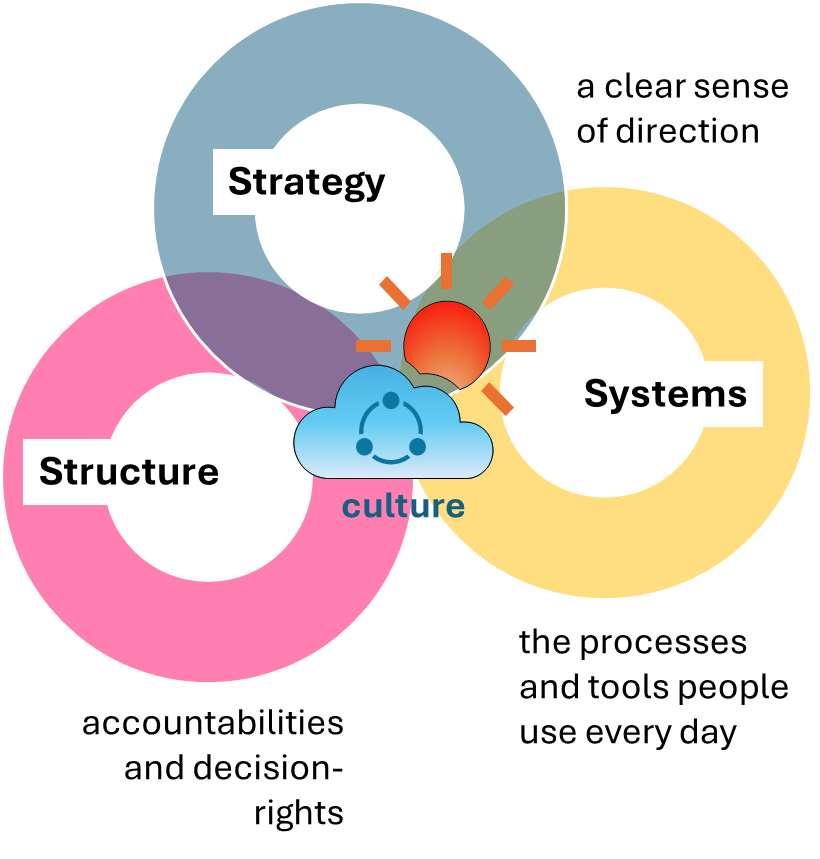

Focusing only on culture is like repainting a crumbling house. It may look better briefly, but the foundations remain weak. Transformation requires coherence between strategy (a clear sense of direction), structure(accountabilities and decision-rights), systems (the processes and tools people use every day).Culture is the the norms and assumptions that emerge from all the above. When one element is changed without the others, friction follows. Culture cannot be transformed without aligning the rest of the system.

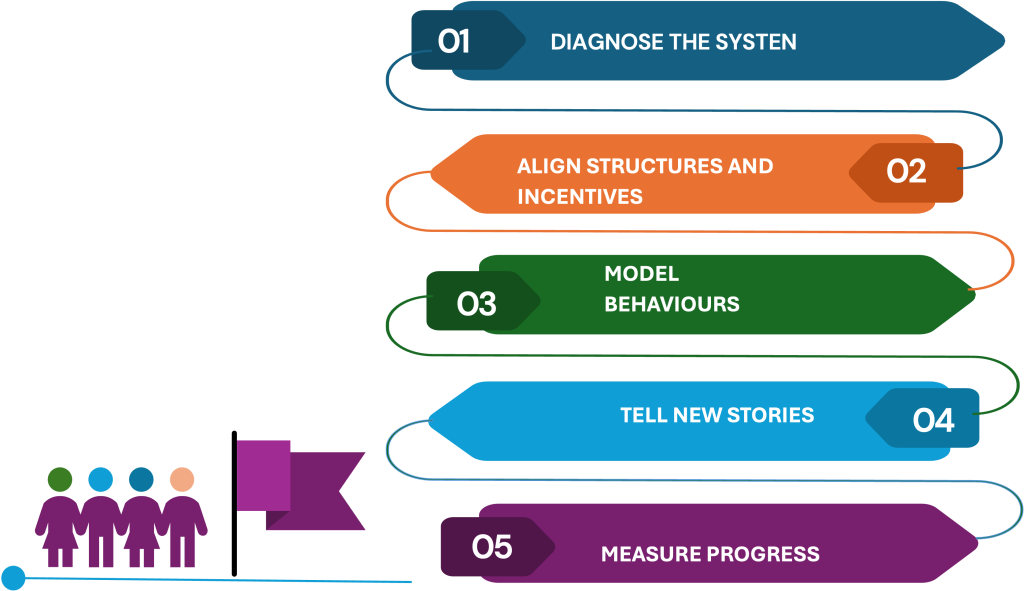

There are ways to challenge and change culture. A basic framework for transformation which moves beyond cultural blames, includes:

Diagnose the system. Look beyond values statements to incentives, behaviours, and processes. Redesign ways of working to reshape everyday interactions and promote positive cultures.

Clarify strategy. Culture should support, not substitute for, clear purpose.

Align structures and incentives. Reward the behaviours you want. If experimentation is punished, a “learning culture” will never emerge.

Model behaviours. Leaders must walk the talk. Leaders shape culture by modelling consistent behaviours. Hypocrisy—preaching collaboration while rewarding competition—kills trust.

Tell new stories. Reinforce positive examples. What gets celebrated or punished quickly defines “how things are done here.”

Measure progress. Track not just outputs but trust, engagement, and adaptability.

Leaders are the architects of culture

The leadership task is to set clear direction, align incentives to desired behaviours, model consistency and fairness, create psychological safety, and take responsibility instead of blaming “the culture” which is a lazy reaction and which avoids harder questions. When leaders externalise culture as something separate from themselves, they miss their greatest lever for change, their own behaviour. Culture matters deeply – it emerges from the interplay of structures, incentives, leadership, and history. If organisations want genuine transformation, they must stop treating culture as the sole culprit or silver bullet. Instead, they should focus on systemic alignment—where culture becomes the by-product of clear strategy, strong leadership, and coherent systems. The next time a report says, “it was a cultural problem,” we should ask: what incentives drove that behaviour? What structures enabled it? What leadership reinforced it? Only then can culture stop being.